A los seres humanos no nos gusta por lo general tomar decisiones. Decimos que sí, que queremos elegir siempre que sea posible, pero la realidad nos suele demostrar que preferimos exactamente todo lo contrario: la comodidad de que nos den las cosas hechas, el refugio de la predictibilidad, la rutina y la certidumbre. Y es lógico, porque si conseguimos que un heurístico u otra persona elija por nosotros, minimizamos el gasto energético. Y es que pensar consume cantidades ingentes de energía. Aunque supone solo el 2% del peso medio de una persona adulta, el cerebro consume más del 20% de la energía que generamos (unos 20 watios al día con una dieta de 2.400 kilocalorías).

¿Puede la IA crear Arte?

Crear arte es un proceso en el que debemos tomar decisiones constantemente. A un trazo le sigue otro, una estrofa continúa con la posterior, a un acorde le acompaña el subsecuente.

¿Puede una IA tomar decisiones?. La forma que tenemos de dar instrucciones a una IA es mediante un «prompt», de forma que con unas someras indicaciones, ésta pueda «centrar el tiro». Pero irremediablemente, el modelo tendrá muchos huecos que rellenar en aspectos que no hemos determinado nosotros en nuestras instrucciones iniciales. Y para cubrir esos vacíos, utilizará información de su modelo de entrenamiento. En el caso de aplicaciones artísticas, esos datos vendrán necesariamente de otras obras anteriores. ¿Y qué referentes artísticos elegirá el modelo?. Tal y como funcionan los LLM en la actualidad, aplicará un cálculo estadístico determinando que la referencia en la que inspirarse sea aquella más popular ó más frecuente en su modelo de entrenamiento.

¿Podrá emocionarnos una creación que ha sido generada usando «valores medios» de referencias del pasado? Creo que la IA podrá generar obras que nos encajen fácilmente dentro de los referentes que consideramos familiares, pero difícilmente podrá sorprendernos. Formalmente, estarán muy bien construidas de acuerdo a unos cánones, pero será complicado que lleguen a generarnos emociones nuevas.

El arte es una cadena de «arrepentimientos»

Un creador toma decisiones típicamente de forma secuencial a medida que avanza en el proceso de elaboración de su obra, mientras que para alimentar una IA el prompt hay que proporcionarlo ex-ante. La IA funciona como si una vez liberado el pincel, no hubiera forma de reenfocar su trazo.

Si has visitado el Museo del Prado en Madrid, habrás observado los «arrepentimientos» en los cuadros de Velázquez. Son aquellos trazos iniciales y bocetos que finalmente el pintor ocultó en capas subsecuentes de pintura.

¿Imaginas el arte sin borrones, sin notas al márgen, sin «arrepentimientos»?

Interpolando en un mundo autorreferente

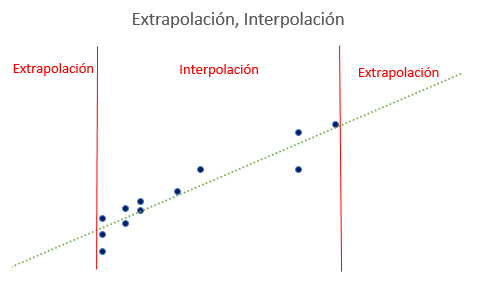

Los modelos actuales son extraordinarios a la hora de interpolar en un campo de conocimiento específico. De este modo, generan resultados realmente coherentes. No es que sean capaces de «entender» el mundo en el que vivimos, pero saben generar datos que encajan como un guante en ese mundo. Además, por una cuestión de diseño, están sesgados según el corpus de conocimiento con el que han sido entrenados.

Como el filósofo Grady Booch nos recuerda, decía Sagan que «la mente humana hace mucho más que predecir«. Es capaz de generar abstracciones, construir teorías sobre el funcionamiento del mundo, y sobre todo, interpretarlo desde el contexto de la propia experiencia, de nuestros objetivos, deseos y sentimientos.

¿Y por que la IA debe reemplazarnos?

La IA no parece que vaya a reemplazar la capacidad creativa de un ser humano en el corto plazo. Pero la pregunta es «¿por qué demonios debería de hacerlo?».

Parecemos obsesionados por predecir cuándo los modelos de lenguaje llegarán a alcanzar la Inteligencia Artificial General (AGI), en vez de enfocarnos en aplicar la IA intensivamente en aquello para lo que ya ha demostrado que es extremadamente útil.

El mundo de la creación es a fecha de hoy, como dice Javier G. Recuenco, «el último santuario humano«.

¿Tecnocenizos o Aceleracionistas?

Como habitualmente nos recuerda César Astudillo, el desarrollo tecnológico no es bueno per sé, pero es ingenuo pensar que se puede parar y poner en pausa por el miedo a potenciales eventos futuros. ¿Qué habría pasado si hubiéramos pausado a Newton, Darwin ó Einstein?

Entre el pesimismo de los tecnocenizos del progreso que creen que la IA nos llevará irremediablemente al desastre y el aceleracionismo tecnológico según el cual la tecnología no es un medio sino un fin y hay que aceptarla sin filtro, hay un término medio mucho más interesante.

Frecuentemente en mi contexto profesional hago a los equipos de Tecnología la pregunta de «¿para qué quieres desarrollar eso?«. Porque no todo lo que se puede hacer técnicamente, debe de ser hecho. Porque debemos empezar desde el primer momento con el impacto en nuestra organización que tendrá aquel desarrollo tecnológico que promovamos.

Necesitamos la «mirada del filósofo», la que se pregunte el «por qué» y el «para qué», poniendo al humano en el centro.

Minotauros ó Centauros

El líder en las organizaciones debe impulsar la adopción tecnológica desde una perspectiva de «Centauro«, donde la toma de decisiones ocurre en la capa humana y la tecnología impulsa con toda su potencia. El liderazgo desde el mero enamoramiento tecnológico con un enfoque de «Minotauro» donde delegamos la cognición al algoritmo y dedicamos al humano a la pura fuerza tractora, lleva irremediablemente al desastre como sociedad.

Siendo responsable de Diseño de Experiencia Cliente en Iberia,siempre nos obsesionaba en el proceso de diseño el dedicar el tiempo suficiente a decidir sobre qué problemas u oportunidades nos estábamos enfocando («design the right things»), antes de zambullirnos de lleno en la ejecución desde la excelencia («design things right»). En esta época de aceleración gracias a la IA, creo que el humano debe dedicar gran parte de su reflexión a asegurarse de diseñar las cosas correctas, y dejar a la IA que una vez decidido qué diseñar y por qué sea ésta la que nos ayude a ejecutarlo de forma correcta.

La emoción de un desfile de moda

Andaba yo en mis pensamientos sobre todos estos asuntos, y dándole vueltas al último informe de Mario Draghi sobre la competitividad en Europa, cuando los amigos de la Universidad de Diseño, Innovación y Tecnología (UDIT) me invitaron al desfile de sus estudiantes del grado de Diseño de Moda en el contexto de la Mercedes Fashion Week.

Ver sobre la pasarela las creaciones de estas jóvenes promesas era emocionante. Pensar que tenemos una generación de chavales explorando «el último santuario humano» en el contexto de la creación, resultaba fascinante.

Según me comentaban, utilizan extensamente la tecnología y la ciencia de materiales para conceptualizar sus diseños. Pero en último lugar, es su muy personal y buen criterio y su ojo para la creación, lo que consigue que nos emocionemos al admirar sus obras.

Mirando al futuro con optimismo

Creo que los que peinamos ya alguna cana tenemos una responsabilidad a la hora de habilitar mecanismos en las organizaciones que lideramos para impulsar una aproximación a la tecnología desde un punto de vista que facilite el florecimiento de lo humano. Pausar de vez en cuando una visión más utilitarista y orientada a la pura eficiencia y replantear si estamos utilizando la tecnología para construir empresas que no solo «interpolen» de forma muy precisa sino que sepan «hiperpolar» como explica el filósofo Toby Ord. Es decir, hacerse preguntas en direcciones que no pueden ser definidas en el contexto de los ejemplos existentes. Explorar territorios y espacios conceptuales en dimensiones no definidas en la realidad existente.

Nunca fue un mejor momento para dedicarse a la gestión del cambio como en tiempos como los actuales. Disfrutemos el viaje.